The Quinn Residences, San Francisco, CA

The Quinn Residences, San Francisco, CA

The Life-Changing Magic of Art in Architecture

Issue No. 002

Art—especially when integrated in architecture—can elevate a sense of place, which in turn strengthens communities.

Art is an expression of human ideals, inextricably linked to culture, identity and community. Art is an aesthetic experience that can energize a space, inspire viewers to transcend their differences, create connection and dialogue. Art — especially when integrated in architecture — can elevate a sense of place, which in turn strengthens communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided the most dramatic example in recent history of the unique power of public art. Creative expression flourished, helping to uplift the sick, reassure the terrified, promote public health, and honor health care workers. A Washington, D.C. campaign distributed more than 1,200 posters by four renowned artists to encourage mask-wearing. Philadelphia’s Fill the Walls with Hope movement plastered hundreds of positive images and words across boarded-up buildings. Muralists saluted front-line heroes with iconic works such as Super Nurse! by the Amsterdam street artist FAKE, portraying a woman in a surgical mask adorned with a Superman logo. A graffiti artist in Germany took a light-hearted approach, painting an image of Gollum from “Lord of the Rings” cradling a roll of toilet paper with the caption, “My precious.”

“Now more than ever, I think people realize the importance of public art,” said Silvia López Chavez, a Boston-based artist whose murals adorn the Charles River Esplanade, Cambridge Public Library, and numerous museums. “It has this capacity to bring joy, to bring wonder, to bring a glimpse of hope when you’re outside during this time that is so challenging and difficult.”

During the pandemic, Presidio Bay Ventures collaborated with four artists to paint murals on a property under renovation in San Francisco to brighten the streetscape and inspire our neighbors. But this was hardly our first effort. Art in architecture has always been a core value for our firm. We believe the two are inextricably linked, and fundamental to authentic placemaking. Integrating art that engages the public and inspires an emotional connection greatly enhances the success of building design.

“Public art can express community values, enhance our environment, transform a landscape, heighten our awareness, or question our assumptions.”

— The Association for Public Art

Our designers and architects strive to showcase the significant contributions visual artists make to the social and cultural life of the neighborhoods and cities where we build. That art can be realized in myriad ways. As the Association for Public Art explains: “Public art is not an art ‘form.’ Its size can be huge or small. … Its shape can be abstract or realistic (or both), and it may be cast, carved, built, assembled, or painted. It can be site-specific or stand in contrast to its surroundings. What distinguishes public art is the unique association of how it is made, where it is, and what it means. Public art can express community values, enhance our environment, transform a landscape, heighten our awareness, or question our assumptions. Placed in public sites, this art is there for everyone, a form of collective community expression. Public art is a reflection of how we see the world – the artist’s response to our time and place combined with our own sense of who we are.”

Public art has been used to articulate shared ideals through the ages. Religious faith has spawned public art as diverse as the Egyptian pyramids, The Parthenon in Greece, Al-Khazneh in Jordan, and the cathedrals of western Europe. Art has reflected reverence for nature, from Chinese landscape paintings of the 5th century B.C.E. to Olafur Eliasson’s 2015 “Ice Watch,” which installed 12 icebergs in the shape of a clock in Paris’s Place du Pantheon. (Onlookers watched them melt over the 12 days of the Paris Climate Conference.) Public art has advocated for social justice and human rights, from the dozens of George Floyd murals that appeared after his death to protest racism and police brutality; to Tatyana Fazlalizadeh’s street art series addressing sexual harassment in public spaces; to Ai Wei Wei’s installation that covered the pillars of Berlin’s Konzerthaus concert hall with 14,000 life jackets used by refugees — a tribute to those who died at sea fleeing war and poverty in the Middle East and North Africa.

“Art is fundamental,” said Susanne Theis, programming director for Discovery Green, a 12-acre park in downtown Houston, which integrated art into its master plan before launch in 2008, and now attracts 1.2 million visitors annually. “While art may be viewed by some as simply decorative, it is a fundamental expression from one human to another. We need that.”

“While art may be viewed by some as simply decorative, it is a fundamental expression from one human to another. We need that.”

— Susanne Theis, Discovery Green

Throughout history, public art has served as a pillar of culture, community, identity, and social discourse. Art can be a powerful universal language, bridging divides, bearing witness to communal experiences, and reinforcing the social and cultural fabric.

“Humans have been producing art before they were even human,” Rafael Schacter, teaching fellow at the University College London and author of “The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti,” told Smithsonian magazine. “We’ve found wonderful cave paintings, Neanderthal decorative art. There’s an innate need to relate our experience, and I think a lot of art is also about relating with each other. It’s about trying to transmit one’s experience to others or create experiences together in a more classical ritual. … There’s this idea that it’s only produced when you have all your other basic needs taken care of, but art is a basic need.”

Architecture, sculpture, and painting were more tightly intertwined in historical periods, such as the ancient cultures of East and West, and in the European Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque periods. In the period after independence, public art in the U.S. largely took the form of war monuments and sculptures of military figures. In the late 19th and early 20th century, industrial tycoons of the Gilded Age built lavish estates, and the arts flourished under their patronage.

Art can be a powerful universal language, bridging divides, bearing witness to communal experiences, and reinforcing the social and cultural fabric.

In 1933, John D. Rockefeller opened his famous center in Manhattan ornamented by a trove of treasures, including murals by José María Sert and sculpture by Paul Manship, Gaston Lachaise, and Isamu Noguchi. (Rockefeller Center was also the unfortunate site of a messy dispute between the tycoon and the Mexican artist Diego Rivera, who included a figure of Vladimir Lenin in his commissioned fresco “Man at the Crossroads.” After Rivera refused to paint over it, Rockefeller had the artwork chiseled off.)

In the late 1940s, developers and architects conceptualized the first shopping malls, integrating art as a core element of activation. Victor Gruen, an Austrian architect who fled the Nazi Anschluss for the U.S., pitched the Hudson department store family on the idea of a shopping center just outside Detroit. When Northland Mall opened in 1954, its 80+ stores emulated the colorful variety of a downtown shopping street, and Architectural Forum magazine heralded the center’s “uninhibited, generous and light-hearted use of art … Northland’s sculpture has the verve, the inventiveness and the simple joy in life of a fine children’s book illustration.”

In 1956, Gruen followed up with Southdale, the first enclosed, climate-controlled mall in the U.S., sponsored by the Dayton department store family. Inspired by the glass-domed Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan, Southdale included a three-story, skylit garden, 21-foot cage with exotic birds, towering sculptures and fountains. Families would stroll through the mall in their Sunday best. “They engaged in an activity believed to be long forgotten, that of leisurely promenading while enjoying flowers and trees, sculptures and murals, fountains and ponds,” Gruen later wrote.

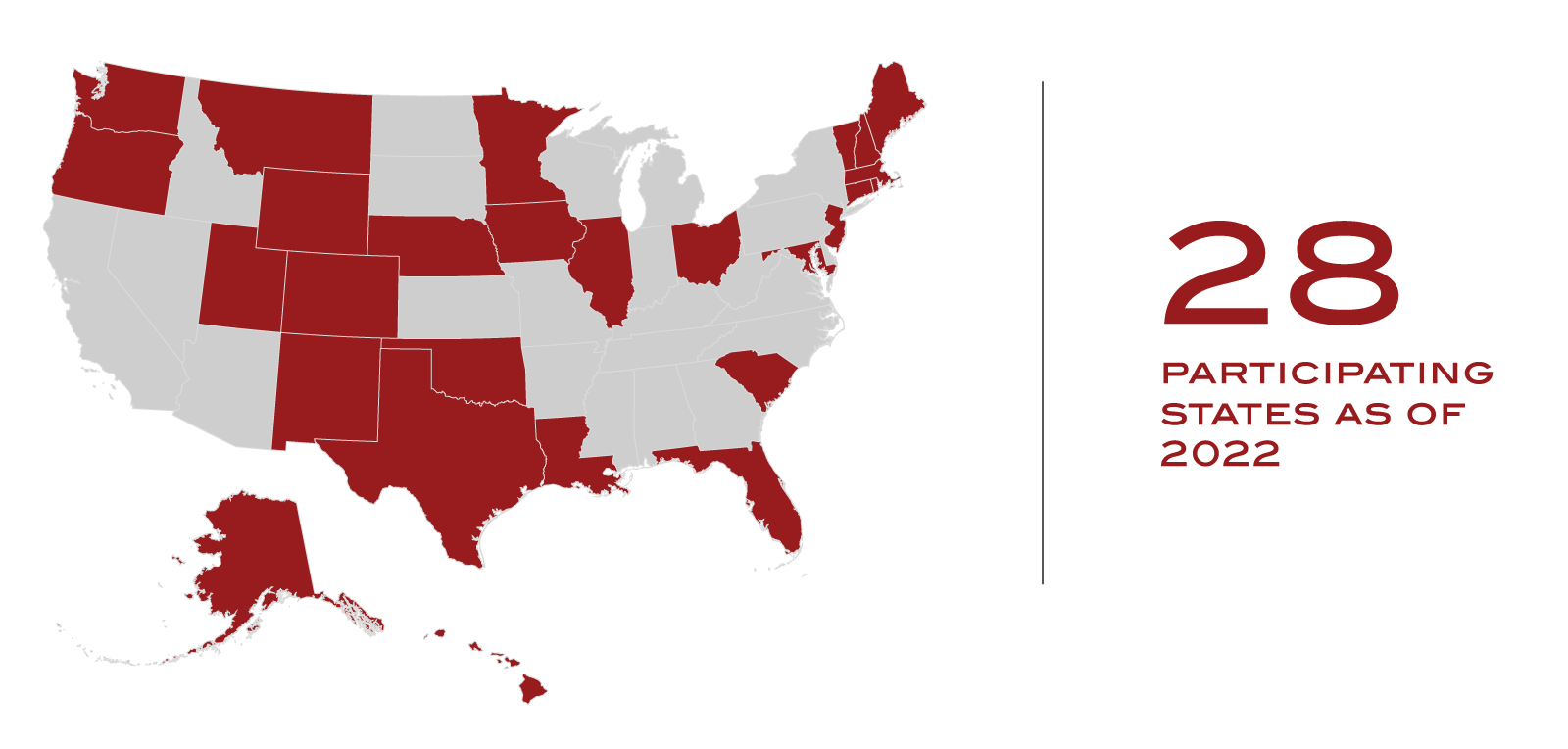

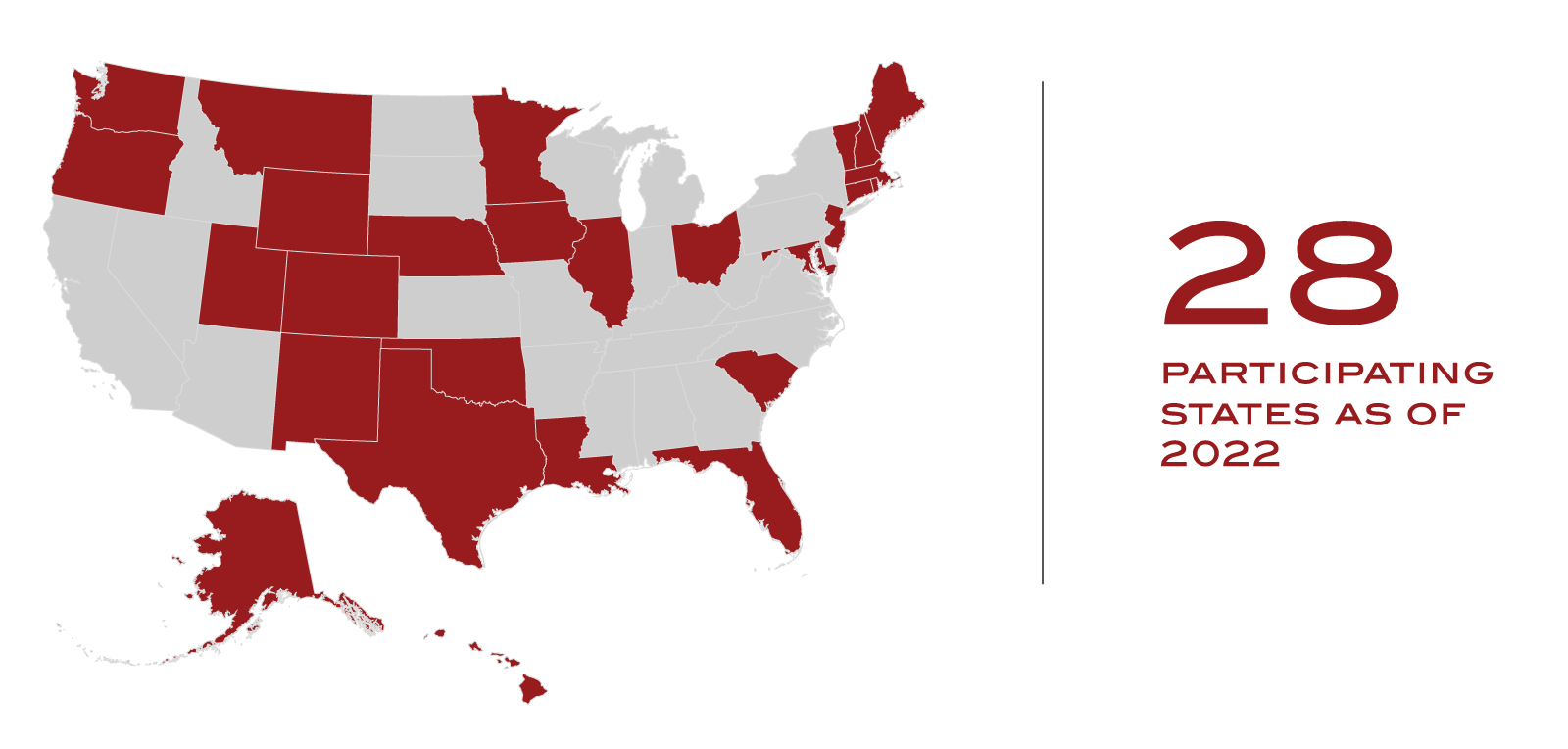

Around the same time, public art in architecture got a financial boost. A handful of cities launched Percent for Art ordinances, in which a percentage of public building costs are set aside for public art. Today, 28 states and dozens of U.S. municipalities employ a Percent for Art program to fund the creation and placement of public art, and some have extended the mandate to cover private commercial development.

In 1962, the General Services Administration (GSA) launched a formal Art in Architecture program, allocating 0.5 percent of the construction costs of each federal project to art. Four years later, the National Endowment for the Arts launched its Art in Public Places program, providing matching grants to communities to support public projects. The first commission was Alexander Calder’s 1969 “La Grande Vitesse” in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Future President Gerald Ford was a Congressman from the area when it was installed. “At the time I did not know what a Calder was,” he said later, “but (it) has really helped to regenerate a city.” The GSA funded Calder’s iconic “Flamingo” in 1974 in the plaza of Chicago’s Federal Office Building.

The 1980s saw a boom in art in architecture, championed by developers such as the late Gerald Hines, who built what is now the world’s largest private real estate investment, development, and management firm. Hines collaborated with prominent architects and occupiers to integrate monumental works in his skyscrapers. “I felt art would increase the awareness of buildings in the public marketplace,” he said in an interview. “And I thought commissioning and buying art would be enriching for the city and the built environment.” Hines acquired pieces from a diverse group of artists, from Henry Moore and Jean Dubuffet to Helena Hernmarck and Muriel Castanis. Hines’ cultural legacy includes the largest Joan Miró sculpture in the U.S., “Personage and the Birds,” at the JP Morgan Chase Tower in Houston, designed by I.M. Pei. The five-story, steel-and-bronze sculpture enlivens and activates the pedestrian plaza with its bright shades of green, red, blue, yellow and black. In New York, the 22-foot gray granite “Lapstrake” sculpture, completed in 1987 by Jesús Bautista Moroles, was commissioned by Hines for the plaza of 31 West 52nd Street, near the Museum of Modern Art. It remains one of the most admired pieces of public art in Manhattan.

“I thought commissioning and buying art would be enriching for the city and the built environment.”

— Gerald Hines

As we observed during COVID-19, art often unifies communities in crisis. During the Great Depression, the U.S. government hired artists to create graphic posters, photography, paintings, and large murals in public buildings – from airports to schools to hospitals. The $35 million effort employed more than 5,000 artists at its peak in 1936, including Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko, as well as thousands of lesser-known artists.

They produced more than 400,000 works over a decade, depicting laborers, rural life, big cities, and technological wonders. Their art emphasized the ideals of progress and democracy and inspired civic pride during a national hardship.

At the same time, public art has also been weaponized to sow division, intimidate, and oppress. The Romans filled public spaces of conquered territories with statues of emperors, and built arches and columns depicting brutal military campaigns. Adolph Hitler was obsessed with plans to erect a massive assembly hall in Berlin and an arch of triumph that would dwarf its counterpart in Paris, according to a memoir by his chief architect. Hitler “was convinced that monumental buildings were powerful weapons, and assumed that political supremacy depended … on erecting structures that would dazzle and intimidate multitudes, inhibiting their bodily disposition to act critically and assertively,” writes Gastón Gordillo, an anthropology professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

On a more local level, art can become the target of misdirected anger and resentment. In 2021, a group of San Francisco street artists defaced the whimsical “honey bear” murals by the artist fnnch, who had painted them on boarded-up stores to amuse residents during lockdown. He also organized a “honey bear hunt” to keep kids engaged. Critics objected to the fact that fnnch was a straight white male originally from the Midwest who had previously worked in tech, and had achieved financial success from his popular artwork. They accused him of “gentrification” and “displacement of local artists” – complaints more reflective of the city’s larger problems.

While people no doubt seek a range of experiences from art, recent surveys indicate that the honey-bear haters are a vocal minority: Most people want art to spread joy.

As the authors concluded, “activities that are fun, lighthearted, and beautiful appeal most.” Asked how arts and cultural organizations could improve after the pandemic, two answers tied: Make them “more fun” (28 percent) and “Nothing—I wouldn’t change them at all.”

While art in architecture inspires happiness, it also offers significant potential to drive higher return on investment. “There is absolutely a business case for art,” said Martha Weidmann, CEO of the consulting firm NINE dot ARTS, on JLL’s “Building Places” podcast. “ROI can include a multitude of different things, like shorter approval cycles, increased market value and recognition, faster sales or lease up, and higher community buy-in and opening support.”

Although the precise ROI can be difficult to track, there are clear examples of instances in which public art has improved outcomes. In Indianapolis, for example, a nonprofit raised $63 million to build an eight-mile paved cultural trail, reuniting six unique neighborhoods that had once been connected by an interurban streetcar. Completed in 2012, the trail elevated an authentic aspect of the city and became a massive catalyst for development. Property values within a block of the trail increased by $1 billion between 2008 and 2014, an Indiana University study found. Developers converted historic structures along the trail into residential and retail space, supporting a burgeoning foodie scene.

Reston Town Center, developed by Boston Properties, offers another example. The urban mixed-use project incorporates galleries, theaters, concerts, art festivals, and installations in its public parks, attracting throngs of visitors. In 2015 the Center’s office vacancy rate was 0.5 percent, compared to a regional average of 16 to 18 percent, and it boasted the highest rental rates in Fairfax County, according to Joe Ritchey, Principal of Prospective Inc., the exclusive office leasing agent at the time. The Center’s “vibrant arts scene provides an extremely positive difference from other business centers in the region and has dramatically increased demand for its office space, which leases faster and for significantly higher rents,” Ritchey noted. “The return on investment is not just financial. The thousands of people who enjoy Reston Town Center’s many amenities and experiences provide a daily testimonial to the positive impact the arts have on a community’s quality of life.”

Claire Cormier Theilke, Managing Director of Asia Pacific for Hines, agreed. “Something that often blows my mind is the ROI on public art,” she said on the “Invest Like the Best” podcast in early 2021. “And not even by famous artists. It can be art by children. Or dynamic art that comes in and just moves. It’s so undervalued. It’s so easy to do and creates so much interest, and in some cases, it’s frankly free. It’s not often thought of.” Presidio is currently developing a framework to measure the ROI of art within its projects.

This calculation includes everything from television and film to museums.) In addition, state cultural investments drive significant benefits for local communities. In fiscal year 2016, the Massachusetts Cultural Council invested $4.5 million in 400 nonprofits that generated more than $1.2 billion for the state’s economy, and employed 32,889 independent contractors, and full- and part-time workers.

At Presidio, art in architecture requires a proactive, organic planning process. Artwork is integrated into a project’s identity, instead of being an additive afterthought to fill negative space. Creative concepts are developed and works of art commissioned in tandem with building plans to achieve a cohesive aesthetic and narrative. At The Quinn, our 38-unit residential project in the South of Market (SoMA) neighborhood, we commissioned an array of custom art pieces and murals from renowned artist Kelcey Fisher – known in the wider art community as KFiSH – at the earliest stages of the process. The theme of the art, dubbed “Controlled Chaos,” informed the brand, identity, and vision for the project – a calm oasis in a bustling neighborhood.

“Working on the project from the beginning really helped the process along; it made it easier to come up with something that would fit the project,” said KFiSH. “If [I come in at the end], I am putting my stamp on the building rather than working with the team to come up with something that’s really cohesive.”

“Working on the project from the beginning really helped the [artistic] process along; it made it easier to come up with [designs] that would fit the project.”

— KFiSH

We saw another opportunity to integrate art in our new life sciences development in San Carlos. San Carlos sits at the heart of Silicon Valley, and the 150,000-square-foot building occupies an extremely prominent site on Highway 101. We received a variance for a five-story atrium that will be distinguished by a suspended helical sculpture representing DNA. Interior building materials and furnishings will take their cue from the piece. Presidio’s projects require close cooperation with local artists, architects, fabricators, and contractors to go from concept to a unique expression of imagination for all to enjoy.

Finally, Presidio Bay views investing in local artists as integral to creating a community of diverse cultures. Our Springline project in Menlo Park features a rotating gallery, activation and incubation space for artists in a city that has few formal galleries, providing an opportunity to showcase their work and support their livelihoods. Our partnership with Youth Art Exchange, a local nonprofit, supports exhibitions of art that emerge from a shared creative practice between professional artists and public high school students.

At Presidio Bay, our work is one piece in a rich historical continuum of art in architecture. We believe art forms the basis of human connection, and thus civic culture and community. At the heart of successful development is placemaking – the creation of a built environment with an organic energy that compels people to engage with the physical location and the other people in the space. Art has the unique power to manifest this energy.